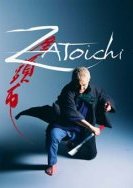

Zatoichi appears as an insignificant blind vagrant roaming the country with no apparent goal, pitylessly slashing through those fool enough to attempt to rob or harm him. On his road, he encouters two orphans who resort to prostitution as a means to exact their revenge from their parents' assassins. Zatoichi soon turns out to be the long awaited arm of vengeance, the instrument of a blind and unforgiving justice.

Around this main plot revolves a number of secondary, light-hearted sub-plots, along which 'Beat' Takeshi takes every occasion to make a fool of himself, managing a good balance of tones between the burlesque parts and the gory fight sequences. Yet as the movie progresses, the various protagonists involved in these sub-plots end up merging in the vengeance dynamics. It is only at the very end that we truly understand what Zatoichi's dedication towards the two orphans stands for, and the final execution is led in an unexpectedly festive way, as in a carnival, or something of the kind, where everyone can rejoice over the disposal of the mock-king, the disguised gang leader Zatoichi has managed to recognize despite his blindness.

The frenetic tap dancing partakes of this orgasmic finale, and the whole music and sound treatment is one of the best thing the movie could aim for. Joe Hisaichi is not around this time and, all respectful of his work as I am, I would be tempted to say it's the better thing we could have expected for that particular film. Come on, what would be the use of Hisaichi's tear-jerking mellowness in the middle of those bloodstreams?

I was rather enthralled by the little drumming pieces whimsically triggered here and there, on any remotely pertinent excuse (the folks' labour actually). Another very interesting effect was the  superimposition of the soundtrack on the buzuki tunes played by the older sister, creating a bitter dissonance perfectly reflecting her inner conflict, upset by her condition, and who finds it hard to go on playing the same beguiling music that originally corrupted her young and innocent brother, while they were desperately attempting to survive in that hostile environment. Even though my French-writing counterparts do not seem to share my opinion, I really found Keiichi Suzuki's score captivating, with a minimalist approach similar to Dominique Petitgand's work, which really fits Kitano's playful mood on this movie. I guess it's all a matter of tastes.

superimposition of the soundtrack on the buzuki tunes played by the older sister, creating a bitter dissonance perfectly reflecting her inner conflict, upset by her condition, and who finds it hard to go on playing the same beguiling music that originally corrupted her young and innocent brother, while they were desperately attempting to survive in that hostile environment. Even though my French-writing counterparts do not seem to share my opinion, I really found Keiichi Suzuki's score captivating, with a minimalist approach similar to Dominique Petitgand's work, which really fits Kitano's playful mood on this movie. I guess it's all a matter of tastes.

To my sense, Zatoichi is Kitano's best film film since The Summer of Kikujiro, paradoxically sharing its carelessness, even though the stakes are radically different here. The talented director also proves he can fit in the new period samurai craze, collaborating with guys such as Tadanobu Asano—with whom he had already sided in Oshima's Taboo, and who also played another fiendish swordsman in Ishii's monumental Gojoe—, and gives a humbling demonstration of cinematographic efficiency to such trendy directors as Riuhey Kitamura and the like.